Okay, apologies again for leaving the blog dormant for so long, but I've been busy (and still am) writing a monster of an article about writing the miniseries, and until that's finished (early next week, I hope!) I'll be forced to keep things fairly quiet on this front.

However, let's weigh in with another Write Environment DVD review, this time featuring Heroes head honcho Tim Kring.

The interview takes us through Kring's entire career: he didn't start out planning to be a writer (shades of George Lucas there), then one job for a Knight Rider episode led him into the freelance writing game which meant writing movies-of-the-week for television for a number of years.

Later on Kring moved into series television, writing for Chicago Hope among others, which led him to create Crossing Jordan, which ran for 6 seasons, and then achieve a huge success with the first season of Heroes.

The first part of the interview is not that riveting, to be honest - but once it hits the 20-minute mark it becomes very good indeed. Kring gives some very honest advice and opinions on the business(if you're an outsider and you're thinking of pitching the next Heroes to a network? Forget it, can't be done), and he offers some excellent insights into what makes a serialized show like Heroes work, and what he and his writing team had to learn in order to make it a success. Pacing is incredibly important - and it's ironic, then, that the lack of good pacing basically ruined the second season.

Another very interesting part is where Kring discusses how the show's enormous appetite for story material didn't lead to the writers running out of gas and ideas, but on the contrary kept generating new possibilities and options all the way through. Great advice many shows could benefit from!

So, after a fairly slow opening this turns into one of the most interesting and thought-provoking releases in the series. And one I have no qualms about recommending to anyone interested in contemporary television writing techniques.

Monday, August 24, 2009

Wednesday, August 12, 2009

The Curious Narrative of Benjamin Button

The Curious Case of Benjamin Button is an interesting film to look at for writers, because it's one of the few mainstream Hollywood films to 'disobey' some of the cardinal rules of screenwriting. But how succesful is it in doing so?

The film is based on a short story by F. Scott Fitzgerald but obviously credited writers Eric Roth and Robin Swicord (there have been many others during the development phase, including Charlie Kaufman) have created a ton of extra material, as there's a framing story which takes place during Hurricane Katrina, and Benjamin Button's life lasts from 1918 to 2003, whereas Fitzgerald died in 1940 and had his protagonist born in 1860 - in Baltimore.

I'll try to focus on the storytelling aspects of the film and leave the other factors out of it as much as possible. Just to get a few things out of the way, the film looks amazing, digital effects are used (as with Forrest Gump) not to create empty spectacle but to tell a story in live-action which would have been impossible to do without the use of CGI, the make-up making Brad Pitt and Catherine Blanchett look old never looks real (sorry, make-up department, I know you've won an Oscar for this, but it just wasn't convincing) and Pitt and certainly Blanchett are miscast.

So onto the film. And of course major SPOILERS! If you haven't yet seen this and intend to go into it 'virginally', stop reading now.

The curiousness of Benjamin Button is that he is born as an ancient baby, and grows younger all the time. So we have a protagonist who suffers from a unique predicament, which is never explained except in terms of magic realism (the story of the clock which ran backwards). Mentally though, he ages normally - at first he's a child trapped in an invalid body, at the end he suffers from dementia while looking like a child and, finally, becoming a real baby.

The film chooses to use a framing story in which a dying elderly woman, in hospital in New Orleans, asks her daughter to read her from a diary - the diary of Benjamin Button. We shift from present to past quite regularly.

Let's focus on this framing device first. In the beginning of the script, there is absolutely no conflict between mother and daughter. She tries to comfort her mother and does whatever she can to please her - i.e. she reads to her from the book.

At first we don't quite know the relationship between Benjamin and , but we surmise they must have been lovers, so it's no great surprise when this turns out to be the case. So there's no mystery and no conflict - the only element of suspense is the arrival of the hurricane - and that only because we know what happened to New Orleans in real life. To be honest, there doesn't seem to be any compelling narrative or thematic reason to use Hurricane Katrina in this film.

Only during the last third of the film is there any conflict when the daughter discovers Benjamin is her real father, and he deserted her when she was only one years of age. She's angry at her mother for making her find out the truth like this, but it lasts just a few moments (the time to try and light a cigarette), before she's okay again and continues reading from the diary.

Benjamin is born on the last day of the First World War. His mother dies in childbirth, and his horrified father leaves him at a nursing home for the elderly which seems to be run by Blacks (the entire film completely sidesteps the racism issue). Benjamin is taken in by a young woman, Queenie, who becomes his de facto mother.

Benjamin grows up among the elderly, so he doesn't stand out. Bit by bit, he is cured of his arthritis and learns how to walk after visiting a prayer meeting. Soon he meets Daisy, a little girl at the time, and falls in love right off the bat. However, they're far too young to stay together forever at this point, so first he goes off to work on a tugboat with an alcoholic Irish captain, sees action in World War II, learns the identity of his real father and inherits their button factory, meets Daisy again who is now a ballerina and temporarily no longer interested in him, sails the open seas with his father's yacht... and finally, in 1962, Daisy returns to him after she's recuperated from a traffic accident that has left her unable to dance again.

So what's wrong with this picture so far (we're now two thirds into the movie)?

Benjamin Button is a protagonist who has it extremely easy.

At no time in the narrative is he thrust into a direct conflict. His youth is ironically fairly idyllic, he becomes rich through no effort of his own, the woman he loves finally comes to him of her own accord. And when earlier on she treats him badly, he just takes it with the same air of benevolent detachment which seems to be his only emotional state for most of the film.

In fact, Benjamin almost seems to be a Buddhist sage at times, though unlike Forrest Gump he doesn't really create major changes in the people he encounters throughout his life. He's more of an observer, even when he takes action (as when he decides to go and work for Captain Mike).

So the film's narrative thrust is hampered by a protagonist who, though he doesn't exactly doesn't want anything (he wants Daisy), does precious little to get to his goal. Good things come to those who wait seems to be the unstated theme of the film - but that's not exactly conducive to keeping the audience emotionally involved.

Moreover, two thirds along the way Benjamin gets his goal - a relationship with Daisy. At this point, the narrative slows to a complete halt.

However, soon after it starts up again, with the first real problem for Benjamin since the film began.

Daisy becomes pregnant, and Benjamin is afraid he won't be able to function as a father because of his condition. He doesn't want Daisy to have to take care of two infants at the same time. So strong is his fear, that he leaves Daisy and his daughter, Caroline, shortly after her first birthday, before she can remember him.

I don't know whether Eric Roth was responsible for this structural twist, but it resembles the narrative of Forrest Gump very much. Forrest also gets his girl long before the end of the film, happiness is achieved, and then she turns out to have AIDS and dies.

In both films, a new problem pops up to give the third act a totally new narrative drive which comes out of nowhere. And here, it doesn't really work.

When Benjamin leaves his wife and daughter, he acts as a coward, even though the film tries to put another spin on his decision. But it's not even a remotely logical decision: when he runs away, Benjamin is approximately fifty years old, which means he's about thirty. So he has at least 15 years to be with his daughter, all the time in the world to explain what's going on with him (except for his father at birth, no one in the film ever reacts to Benjamin's condition as something appalling, horrifying or unacceptable, why should his daughter be any different?). And by the time he does regress, his daughter would be an adult herself and be able to help Daisy look after her dad.

Sure, there is a heartbreaking moment when the adult Caroline discovers all the birthday cards Benjamin wrote to her but never sent; but his "sacrifice", such as it is, comes across as shallow and selfish, rather than as a noble gesture. Moreover, we've never seen Benjamin upset or moved, not even at Queenie's funeral, and he considered her as his real mother. So why would he get so upset about his perceived inability to be a father?

The reason is: there has to be a plot. Although this film is largely character-focused, at this point all psychological realism or logic is ignored in order to have something happen to the main character. Because otherwise, he'd just have stayed with Daisy and Caroline, and there would have been nothing left to tell at all in either storyline up till the moment of his encroaching dementia and his death.

Interestingly, the original short story has Benjamin born as a mental adult, and he regresses to a child and eventually a newlyborn infant on both the physical and mental level. In his youth, his dad forces him to go to school and play with children even though he'd rather smoke cigars and ponder philosophy; when his wife gets older, he becomes disenchanted with her and leaves to fight in a war; and as he becomes a child again, he goes to kindergarten together with his grandson and finally shows interest in toys and games. It's a far more conflict-laden way of handling the material, and one cannot help but wonder why all these ideas were ditched.

Instead, we have - two storylines with nearly no conflict, and that conflict only coming in the third act of each story

- a largely non-active main character who almost never initiates action

- an epic love story in which one of the characters (Daisy) is actively unlikeable and not very interesting, making us wonder why Benjamin is so besotted with her

- a major decision by the main character which alienates him emotionally from the viewer.

On top of this, there's the matter of theme. Though many themes are mentioned throughout the film (you can do anything, fate cannot be escaped so just accept it), there doesn't seem to be one theme that binds everything together - and certainly not a theme which could only be told with precisely these characters in exactly these conditions. There is no pressing reason why Hurricane Katrina should be the backdrop of the framing story; and there is no big theme or metaphor which needs the reverse aging idea to be communicated to the audience. In Forrest Gump, the theme and the narrative did fit together. Here, it's almost like we're being offered a semi-sequel which doesn't really make sense. Benjamin Button is to Forrest Gump what Evan Almighty is to Bruce Almighty...

Could the narrative have worked better than it does now, even with the same non-active protagonist? I think it could have. There's one sequence (Daisy's car accident) which has a playfulness in the storytelling which reminded me of Amélie Poulain (another film with a very passive protagonist, and not one of my favourites though it probably is one of yours). It shows every detail which lead up to the accident and then also shows how it could have been avoided. If there had been (far) more risk-taking of this nature, the film would constantly have received energy from its narrative unpredictability.

Another way to render the narrative more powerful would have been to tell less and show more. The diary becomes a crutch. For instance, when Benjamin leaves his family, we don't see him suffer, have scenes where we see him regret his decision, or whatever. We just see a travelogue of India and then, somewhat later, a scene where he returns to Daisy for no special reason except to show Brad Pitt as a glowing twenty-year old. By jumping through time, and having the events in the story continually told to us even when they're being shown, the narrative keeps us at an arm's length even when we should be totally entranced by the 'great love story to transcend the ages' which it tries to sell us. But when your female character is cold and selfish and your lovable hero deserts the people who need him most, that sort of becomes a lost cause.

Sunday, August 9, 2009

DVD Review: The Write Environment: Sam Simon

Sam Simon may not be a household name to everyone, but his career is second to none.

He's worked on Taxi (becoming the showrunner in its final seasons), Cheers, The Tracey Ullman Show, The Drew Carey Show, The George Carlin Show and a little animated series you may have heard about once - The Simpsons. Add 9 Emmy's and 13 nominations to the mix and you have a career most writers don't even dare dream about.

On top of which he's running a dog foundation, he's Jennifer Tilly's ex-husband and he's a world-class poker player.

Truth be told, the two latter aspects of Simon's life aren't mentioned on this DVD. But as you may imagine there are more than enough topics to talk about which are of interest to screenwriters everywhere.

Simon entered the TV world via animation (he was a cartoonist in college), and from there on managed the incredible feat to write a spec script for Taxi which was immediately bought and produced.

On The Simpsons, he was responsible for developing several of the extra characters which make up the tapestry of Springfield. His observations about the difference in writing for an animated sitcom vs. a traditional one are quite interesting. There is no mention, however, of his leaving the show in 1993 (although his name remains on the credits and he still earns a lot of money from the show).

Throughout the DVD, Simon remains a friendly, soft-spoken and generous interview subject. The only person who he is not too enthusiastic about is Family Guy's head honcho Seth McFarlane, because of the similarities between the two series. It was quite surprising, then, to read a Sam Simon interview in which he admitted to becoming a monster while running a show, and it eventually made him quit the business.

If you're interested in any of the shows Simon worked on or ran, this DVD is definitely worth getting. To be fair, I should mention that there aren't as many immediately applicable insights or tips to be found here as on some of the others in the series.

He's worked on Taxi (becoming the showrunner in its final seasons), Cheers, The Tracey Ullman Show, The Drew Carey Show, The George Carlin Show and a little animated series you may have heard about once - The Simpsons. Add 9 Emmy's and 13 nominations to the mix and you have a career most writers don't even dare dream about.

On top of which he's running a dog foundation, he's Jennifer Tilly's ex-husband and he's a world-class poker player.

Truth be told, the two latter aspects of Simon's life aren't mentioned on this DVD. But as you may imagine there are more than enough topics to talk about which are of interest to screenwriters everywhere.

Simon entered the TV world via animation (he was a cartoonist in college), and from there on managed the incredible feat to write a spec script for Taxi which was immediately bought and produced.

On The Simpsons, he was responsible for developing several of the extra characters which make up the tapestry of Springfield. His observations about the difference in writing for an animated sitcom vs. a traditional one are quite interesting. There is no mention, however, of his leaving the show in 1993 (although his name remains on the credits and he still earns a lot of money from the show).

Throughout the DVD, Simon remains a friendly, soft-spoken and generous interview subject. The only person who he is not too enthusiastic about is Family Guy's head honcho Seth McFarlane, because of the similarities between the two series. It was quite surprising, then, to read a Sam Simon interview in which he admitted to becoming a monster while running a show, and it eventually made him quit the business.

If you're interested in any of the shows Simon worked on or ran, this DVD is definitely worth getting. To be fair, I should mention that there aren't as many immediately applicable insights or tips to be found here as on some of the others in the series.

Wednesday, August 5, 2009

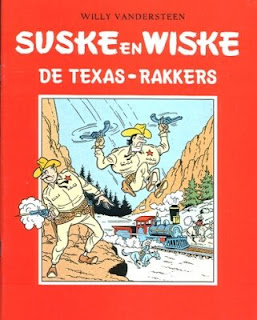

Interview: Dirk Nielandt, writer of 'De Texasrakkers'

Dirk Nielandt is primarily known in Flanders as an author of children's books, and the last few years he's been quite active as a writer for television as well. Recently he added a major feather to his cap when he became the writer for the very succesful Flemish animated feature De Texasrakkers. Dirk graciously consentend to an interview, and shared his experiences on writing the first Flemish 3-D computer-animated feature with us and, through the magic of the internet, the world...

1) How did you get approached to write the script for Texasrakkers?

I was working on a television project for Skyline Productions, the production company of De Texasrakkers (Texas Rangers), when Eric Wirix (ceo Skyline and producer of Texasrakkers) and Mark Mertens (director of Texasrakkers) came up with the idea to make an animatied tvseries with Suske and Wiske (in UK known as Spike & Suzy or Bob & Bobette in French) as main characters.

For those who don’t live around here: Suske and Wiske are comic book characters that are world famous in Belgium and Holland. They have been popular since the fifties. Generation after generation grew up with their adventures.

Willy Vandersteen (1913-1990), the spiritual father of Suske and Wiske, sold millions and millions comic books of his action-adventure-comedy characters, and entertained whole generations with brilliant and often hilarious storytelling. Until today the books remain popular and are rock-solid sellers.

I was (and still am) not only a huge fan of Suske and Wiske, but also worked for some years as editor-in-chief of Suske en Wiske Weekblad, a weekly comic magazine. I also wrote ‘Suske en Wiske’-books for kids who are just learning to read. So I knew the world of Willy Vandersteen and ‘Suske en Wiske’ quite well. I was happy and honoured when I was invited to participate in the brainstorm sessions for the animated tv series.

2) You mention an animated tv-series, but Texasrakkers is a 85 minute 3D-animated feature film!

Yeah, right. We kicked off brainstorming for a tv-serie, then started to develop a 50-minute tv-movie that could be divided into 5 episodes of ten minutes each.

Then the decision was made to go all the way for a feature. I guess the project grew and the ambitions grew. Things kept moving. That was fun. We also started develop

ping a completely different story for the feature. It was like starting from scratch after months of working on the tv series, but on the other hand it wasn’t, because talking and writing the television movie prepared us for the more serious work.

3) You're a writer of children's books and a scriptwriter for television. Was it difficult to make the transition to writing the screenplay for an animated feature? Did you have to learn/use new skills as a writer?

It certainly is something completely different, so I definitely had to use different skills. Fortunately a year before we started writing I participated in a screenwriting development course (North by Northwest in Denmark) where I developed a feature screenplay for an animated feature, based on one of my own children's books. I worked under the supervision of Hollywood animation-screenwriter Philippe Lazebnik (Prince of Egypt, co-writer of Shrek, etc). In the end that script didn’t get produced, but I certainly learned very useful skills that helped me during the development of Texasrakkers.

4) 'De Texasrakkers' is an adaptation of a comic book. At first sight, this would seem to lend itself extremely well to a movie adaptation. What turned out to be the biggest difference between the two media for you?

The biggest difference is ‘structure’. Some comic books are written in a structure that is easily transferable to a moviestructure, but Texasrakkers isn’t :-)

And that’s understandable. You should know that the original book was published in 1959 and its structure was dictated by the fact that it was a newspaper comic. Every day the newspaper published an episode of Suske and Wiske a the length of half a page in the book. Ususally this meant that Vandersteen wrote and drew half a page a day. He produced four Suske en Wiske albums a year. Even for that time it was a hell of job. There was no time to start structuring the whole story before starting. The story was developed day after day after day after...

Vandersteen was a man with a very rich imagination. He was a brilliant storyteller. To keep his newspaperreaders hooked, he ended every daily epsiode with a cliffhanger. Usually every daily episode also contained a joke. This meant that in the end, when the story was published as a book, the structure was... eh... non-existant. That didn’t disturb the Suske and Wiske-readers at all. On the contrary. It made Vandersteens work original and funny and witty and wonderfully chaotic. It is part of the charm of his work. His stories were wild, funny, exciting and very original.

But unfortunately this structure (or the absence of structure) could not be transferred to the big screen. The flow of the book would not work for a feature. So we had to re-think the structure completely. We had to re-think the plot all over. The only thing we wanted to keep by all means was the soul of the album, the spirit of Vandersteen, his unique voice of storytelling. That was quite a challenge, but it was also part of the fun of writing this movie. How to translate the magic of Willy Vandersteen to a modern feature that would still fascinate an audience that is less familiar with the early Suskes en Wiskes descending from their parents childhood.

5) Why did you choose the Texasrakkers?

Good question. There are 300 Suske and Wiske albums to choose from (300+ by now), so which story to choose... That was a hard one.

One thing we were absolutely convinced of was that it had to be a Willy Vandersteen story. It had to be a story he wrote. Not that his succesors didn’t do a great job, but Vandersteen is the founding father. He has written the ultimate Suskes en Wiskes. So it had to be one of his stories, which limited our range of choice. I don’t remember exactly how long the remaining list still was, but it was still huge (sigh).

Another important issue to take into account was that almost every adult in Belgium and Holland has his or her favourite album(s). Almost everyone has a couple of Suske en Wiske-books that transports them back to the magical age of 10-12 years old. So for every story we choose, we had to disappoint a lot of people who would absolutely be sure we made the wrong choice because album nr 98 or nr. 123 or nr. 44 or ... is in their memories the most fantastic, faboulous, wonderful Suske and Wiske-story of their childhood.

Mission impossible? It was Eric Wirix who had the idea to choose a genre story. Some of the most popular albums were stories based on popular Hollywood films of that time. Suske and Wiske covered almost every film genre: sci-fi, action, romantic comedy, you name it! James Bond, Planet of the Apes, etc. So we decided to start with a genre that is more or less the father of all movie genres: the western. And look... Suske en Wiske en de Texasrakkers, a real western, was in our top 10 list anyway...

6)Was there sufficient material in the original book to fill the movie? Or did you have to cut things or add material to get the right length for the film?

There was enough material. We had to kill plenty of darlings (the rock that threatened to destroy Dark City, for those who remember the book) in order to make the story work properly. We also had to cut some characters that were too archaic (the story is from 1959, remember). But the album was so rich and contained so much material that there was plenty to fill the movie.

7) Did you collaborate mainly with the director, or with the animators as well? Did they have specific demands you had to take into account?

From the beginning of the writing process I collaborated with both producer Eric Wirix as well as the director Mark Mertens. We held brainstorm sessions at the Skyline office on a regular basis. After these sessions I went home to write and rewrite. Some weeks later we sat together again and discussed the new outline, treatment or synopsis, depending the stage of development we were in. The first draft was really the result of the collaboration of this small writing team, all die-hard fans of Suske en Wiske. We continued working like this until we had a first draft that everybody was happy with.

Then my work was done. Guy Mortier, the ex-editor-in-chief of the weekly magazine Humo, well known for his sharp and witty pen, polished the script, spiced it up with great jokes and sharpened the characters. I think he did a great job.

After that the actors started working with the script. The voices were recorded and once that was done the team of animators started to work. I didn’t have contact with the animators at all (and there is no reason why I should have). More then 100 animators were working on it in Liège and Luxembourg. A hell of a job for the two directors Mark Mertens and Wim Bien. They supervised, directed, managed this huge team. Quite an acrobatic job. It took them a lot of stress and a couple of sleepless nights, but they did great!

8) Did you have to include a lot of visual information in this script which you wouldn't normally do?

No. Perhaps because one of the directors was part of the writing team, he filled in the sets and visualized it in 3D. No need for me to put it in the script. But I also think it is a misunderstanding that scripts for animated features automatically need more visual information. We didn’t create a completely new world that needed to be described. It was the Wild West, how much description does that need? It was also an action movie, with some serious action and fight scenes. Obviously those scenes didn’t need dialogue but a detailed description of the action.

9) The climax of the comic book features a deus ex machina - did you keep this or was it changed for the film?

A deux ex machina in a family film is a disaster, a rip-off and absolutely not done. As mentioned before, we re-thought the main plot of the story. We turned it into a western with a who-is-the-bad-guy-behind-the-mask-(a wodunit)-plot. ‘Who is Jim Parasijt really?’ is the question that is pushing the story forward in the second and third act. The answer to that question had to be a surprise ànd had to make sense in the end.

I’m not gonna spoil the fun for those who haven’t seen the movie yet (go and see it!!), but I think we succeeded in avoiding to rip off the audience with a deus ex machina and still surprise them with the answer to this main question.

10) Were you able to keep a lot of the original dialogue, or did you have to do a lot of work to make it work in the screenplay context?

Some verbal jokes were kept, but as most of the scènes in the movie are different from the book, most of the dialogue is different too. And anyway... dialogue, how we speak, use of words has changed a lot since 1959, so obviously it was updated.

11) What was the most difficult thing about writing this screenplay?

Re-structuring a story that was written in the fifties to a modern well-structured screenplay that kept the original soul of the album and would honour the work of Vandersteen.

We also never lost focus that we had to respect the memories of all the Suske en Wiske-fans. Lots of them are very protective of their heroes and we didn’t want to shock them by creating something very different from the original characters.

12) And what was the most rewarding?

Seeing the result of all this labour on the big screen and listening to the reactions of the kids and their parents. It’s great when they laugh when they’re supposed to laugh, thrill when they‘re supposed to be thrilled and leave at the end of the movie with a big smile on their face.

This movie is really the accomplishment of a big team. Writers, producer, directors, animators, actors, designers etc all put a lot of time and energy in this project. All for the love of Willy Vandersteen's work, trying to capture his spirit and update it for the screen. It was fun working on it and right now I’m hoping we can start writing the sequel;-)...

Best of luck with that, and a big thank you to Dirk for taking the time to talk to us and let us know what it's like to work on a major animated feature!

Monday, August 3, 2009

DVD Review: The Write Environment: Joss Whedon

The first DVD in the series cleverly features Joss Whedon, probably the writer/showrunner with the most extensive and loyal fanbase in all of television.

Will loyal Whedonites get their money's worth from this interview with their idol?

Well of course they will. Joss Whedon is not only a writer with a very identifiable voice, he's also an excellent raconteur who somehow masters the art of being both arrogant and humble at the same time.

The interview takes place at his home, in his writing room, which naturally is a treasure trove for fanboys and -girls. The interview is wide-ranging, touching upon all parts of Whedon's career (writing for movies, television, comics, and producing and directing). We learn the identity of his favourite character (in a way), he discusses how and why he resurrected Colossus in his Astonishing X-Men run, he talks about the upsides and downsides of script-doctoring in Hollywood and reveals why he no longer does it.

Along the way there are plenty of humorous anecdotes, several nuggets of wisdom for writers to ponder (for instance, the difference between writing for television and writing for film is discussed, as is Whedon's dislike of 'reset' television, and his predilection for mixing genres (and it's not done on a whim or just to be 'interesting').

In short, an excellent and entertaining way to spend approximately an hour in the company of one of television writing's true originals, and an absolute must-have for anyone who is even just a tiny-little-bit of a Whedon fan.

Will loyal Whedonites get their money's worth from this interview with their idol?

Well of course they will. Joss Whedon is not only a writer with a very identifiable voice, he's also an excellent raconteur who somehow masters the art of being both arrogant and humble at the same time.

The interview takes place at his home, in his writing room, which naturally is a treasure trove for fanboys and -girls. The interview is wide-ranging, touching upon all parts of Whedon's career (writing for movies, television, comics, and producing and directing). We learn the identity of his favourite character (in a way), he discusses how and why he resurrected Colossus in his Astonishing X-Men run, he talks about the upsides and downsides of script-doctoring in Hollywood and reveals why he no longer does it.

Along the way there are plenty of humorous anecdotes, several nuggets of wisdom for writers to ponder (for instance, the difference between writing for television and writing for film is discussed, as is Whedon's dislike of 'reset' television, and his predilection for mixing genres (and it's not done on a whim or just to be 'interesting').

In short, an excellent and entertaining way to spend approximately an hour in the company of one of television writing's true originals, and an absolute must-have for anyone who is even just a tiny-little-bit of a Whedon fan.

Saturday, August 1, 2009

DVD review - The Write Environment: Phil Rosenthal (Everybody Loves Raymond)

You might be familiar with the 'Dialogue' DVD series, in which movie screenwriters are interviewed about their career and their craft. Well, you may be interested to know that there is now a complementary series available, namely The Write Environment, which does the same for television writing. Each DVD features a show runner being interviewed in his writing environment by Jeffrey Berman, who's also the executive producer for the series. I'll be reviewing every installment as I watch them, so you can decide whether the disk should be in your collection of screenwriting resources or not.

The first disc I watched features Phil Rosenthal, the showrunner of Everybody Loves Raymond. The interview takes place in his guest house, which gives the entire proceedings a relaxed atmosphere. However, there's plenty of excellent advice on sitcom writing to be found here.

Rosenthal is (naturally) a funny man, with a fine line in self-deprecating humour. He also comes across as a genuinely nice person - in fact, some colleagues at work have visited the Raymond writer's room when the show was still being aired and told me that Rosenthal actually sent his writers home at a normal time, so they could interact with their families and have the necessary experiences to fuel their writing.

This relates to one of Rosenthal's main points: for him, 'write what you know' is essential. Since you are unique as a writer and a person, tell stories about your experiences, as they are what sets you apart from your colleagues (and rivals).

Another very important element of the success of Raymond is the relatability of the characters. This is NOT the same as likeability - the characters may be mean or selfish, but the audience can understand their attitude, or recognize it in themselves or the people around them. Rosenthal says he's even received letters from people from Sri Lanka telling him their parents are just like Ray's...

All in all, a very good interview and a very interesting disc for anyone interested in learning more about classic American-style sitcom.

And you can get this DVD and the others from the series right here:

The Screenwriter's Store

The first disc I watched features Phil Rosenthal, the showrunner of Everybody Loves Raymond. The interview takes place in his guest house, which gives the entire proceedings a relaxed atmosphere. However, there's plenty of excellent advice on sitcom writing to be found here.

Rosenthal is (naturally) a funny man, with a fine line in self-deprecating humour. He also comes across as a genuinely nice person - in fact, some colleagues at work have visited the Raymond writer's room when the show was still being aired and told me that Rosenthal actually sent his writers home at a normal time, so they could interact with their families and have the necessary experiences to fuel their writing.

This relates to one of Rosenthal's main points: for him, 'write what you know' is essential. Since you are unique as a writer and a person, tell stories about your experiences, as they are what sets you apart from your colleagues (and rivals).

Another very important element of the success of Raymond is the relatability of the characters. This is NOT the same as likeability - the characters may be mean or selfish, but the audience can understand their attitude, or recognize it in themselves or the people around them. Rosenthal says he's even received letters from people from Sri Lanka telling him their parents are just like Ray's...

All in all, a very good interview and a very interesting disc for anyone interested in learning more about classic American-style sitcom.

And you can get this DVD and the others from the series right here:

The Screenwriter's Store

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)